Communication Challenge 2 – Post Mortem

I’m glad I posted in the nadir.

On Friday, both classes took to the field and tried to make a go with their half formed plans for the Communication Challenge.

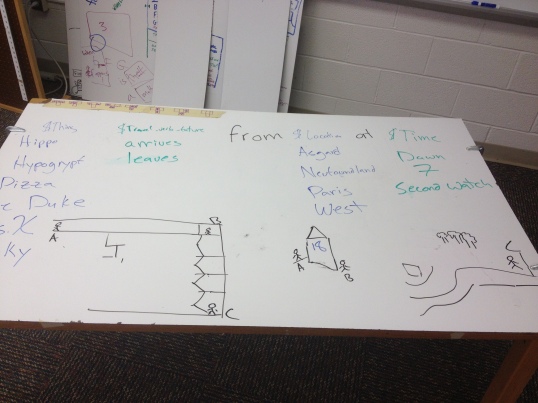

Short summary: Teams have to pass a message over/around/through a barn, then across a large section of open field, without revealing it to observing students.

I need to remember that despite my overwhelming teacher-concern, leaving the building is almost always a good move. Opening those doors spikes the students’ perceived “realness” of the moment., and their nebulous plans (like “use Morse code”) had to turn into real action (like…stopping by the printer to grab some Morse code cheat sheet).

Let me poke at that one group for a bit. First, after they asked if “Morse code was legal,” their immediate response was … to do nothing. They had found a cowbell in the room (I planted it on the parts shelves earlier in the week) and determined that you could probably hear it across the long distance. Since Morse code was legal, then they all knew they could just “use Morse code.” That idea, that named thing, sat in their brains and filled up all the space, a perfect response to a short-answer quiz question. “We’ll use Morse code” sat contentedly in their middle of their plans and lied to them.

It’s not until they’re running down the stairs that they think to print up a Morse alphabet list. Because “Morse code” was so beguiling, so obviously RIGHT, they didn’t give any thought to implementation. So it wasn’t until they were in the midst of their 3 minute section, that the reality of banging out one of these messages letter by letter.

In the end, “Dr. X arrives at Asgard at dawn” reached the recipient as “U G B Q D wait, start over! Oh my god, Was that a dash? I have no idea what you’re saying!”

<sniff> Sorry, just got something in my eye.

That’s an extreme example of what I saw throughout both classes. Every ideas, the strong and the harebrained, smashed hard up against the real world.

Shouting a color name seems easy, but three story barns play funny games with sound waves. People halfway across the field could hear the coded message, but the poor guy at station B was in a sonic dead zone.

It takes a surprisingly long time to make sizable squares out of masking tape.

Even if you’re a pretty good middle school football player, 120 yards is a really, really long throw.

One major goal for this year’s class is to make active & public reflection an obvious and expected part of the learning process, without relying on graded notebooks or points-for-blogging. This exercise made clear how important that reflection step will be throughout the year.

In their basic school-aligned state, middle school students are impatient. They consistently overestimate their ability and heroically underestimate complexity. Those two traits combined mean that I should expect a > 80% failure rate for any one-shot challenge. I’m convinced that a day spent testing horrible ideas is 10x more productive than a week asking them to “think through” their first thoughts. But something needs to happen after that, some enzymatic trigger that processes frustration into grit and new ideas.

“I think that my group should’ve thought of more than just one ideas so if one didn’t work then we would have another.”

Yeah! Focused on the design process instead of the specifics of the challenge, here’s a piece student reflection that gives me hope!

“I think we need to make a mortar to fire the football across the field.”

… but they’re still 7th graders.